Ashlynn Dunbar Refuses to Shut Up and Dribble

Oklahoma’s two-sport grad student speaks on race, leaving San Diego State, and the undertones of “stick to sports” culture

Thanks for reading the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter. If you like our work, be sure to check out our stats site, our podcast, and our social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. You can also buy Her Hoop Stats gear, such as laptop stickers, mugs, and shirts!

Haven’t subscribed to the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter yet?

Oklahoma two-sport standout Ashlynn Dunbar isn’t afraid to speak out in the face of injustice. In the weeks since the murder of George Floyd sparked national calls for reform, she’s been on the front lines. But it wasn’t always that way.

Before transferring to Oklahoma in 2019, Dunbar spent three seasons on the volleyball team at San Diego State — three long, arduous seasons of being told to stick to sports.

"I was very uncomfortable — I never wanted to speak on anything," she says. "I was more in this mindset, 'I just need to make it through. Whatever it takes, I'm gonna keep my mouth shut; I'm gonna do what I'm told.'"

By the end of Dunbar's junior season in 2018, just making it through was no longer an option. "I ended up going through some mental health issues,” she says. “I was just like, 'I can't take this anymore … I don't deserve this. I'm not going to go through this anymore.'"

“When we're not on this campus or we're not in our uniforms and we're not playing a sport, our lives are in danger.”

—Ashlynn Dunbar

After the season, Dunbar decided to step away from the sport she loved. Coaching a youth team the following spring, however, rekindled her volleyball flame. "I'm a very huge competitor — I love to play the game; I love to compete," she says. "I was just like, 'I deserve a senior season.'"

So Dunbar entered her name into the transfer portal and began her search for a new school — with one priority at the top of her list. "It was definitely important for me to feel comfortable … knowing that I would be okay," she says. "I was like, 'I don't want to be in [the] exact position … that made my mental health deteriorate.'"

She soon connected with the Oklahoma volleyball coaching staff, and they promised her they'd put Ashlynn the person before Ashlynn the athlete. "They kept their word," Dunbar says. "I've never once not felt supported by them; I've never once felt uncomfortable."

After leading the Sooners to their first NCAA Tournament appearance in five years in her final season of volleyball in fall 2019, Dunbar transitioned to basketball, where NCAA eligibility rules would allow her to finish the 2019-20 season and play the full 2020-21 season. The culture of the basketball program has been just as strong as that of the volleyball program.

“The [basketball] team is phenomenal — they're just a great group of people, and it's really such a supportive atmosphere,” Dunbar says. “It's overwhelming and it's emotional because I came from the complete opposite.”

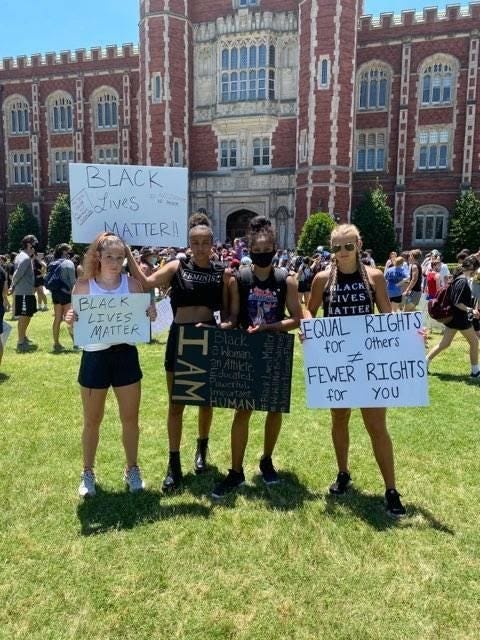

Ashlynn Dunbar (second from right) and fellow protesters gather in front of Oklahoma University’s Evans Hall at a protest on June 6. (Photo courtesy of Ashlynn Dunbar)

The poisonous culture that infected the San Diego State volleyball program has infected fanbases for generations — “stick to sports” culture in America is nearly as old as American sports themselves. From the “release for the social pressures of industrial society” that was 19th-century baseball to the vitriolic opposition against activists like Muhammad Ali and Billie Jean King, (predominantly white male) fans have done their best to suppress the off-court voices of the same players whose on-court success they cheer for since long before Donald Trump called NFL protestors “sons of b****es” or Laura Ingraham told LeBron James and Kevin Durant to "shut up and dribble."

Don't try that line on Dunbar though. She’ll kill it quicker than a volleyball.

"It's important for us as athletes to step up and say something and speak, so people do understand that we're not just athletes — we're human beings," Dunbar says. "Everyone has the right to speak out on how they feel and what they've experienced, especially as Black males and females in America, because that's who we are before we're an athlete. We're human beings, we live our regular daily lives, we go out in the public, we go out and do these things, and our lives are threatened every single day. When we're not on this campus or we're not in our uniforms and we're not playing a sport, our lives are in danger.”

“As college athletes … we have so much power and such a powerful voice.”

—Ashlynn Dunbar

The backing of teammates and coaches at her new school has “made the whole world of a difference” for Dunbar, but it cannot change the fact that she is Black in America and can tell countless stories of racism. There was the time a driver pulled up beside her at a stoplight and called her the N-word. Or the time when her father, then a member of the Harlem Globetrotters, was mistakenly arrested with two of his teammates. The three men were held at gunpoint — on the ground — because they “matched the description” of three men who had robbed a jewelry store. The police were looking for three men of average height. Louis Dunbar is 6-foot-10.

To silence athletes like Ashlynn Dunbar is to silence vitally important stories such as these. To tell athletes to stick to sports ignores the fact that racism doesn’t care that they play sports — drivers who use racial slurs or police officers who racially profile people don’t treat Black people any differently simply because they are athletes.

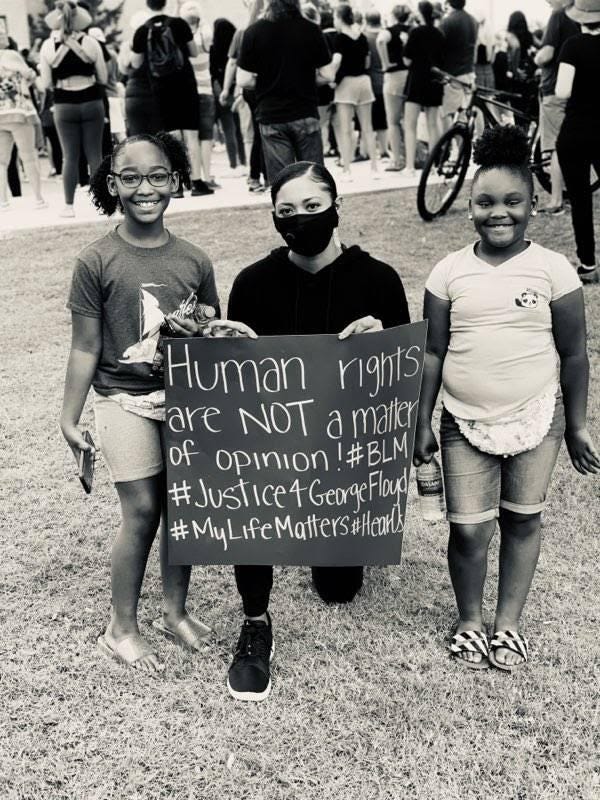

Ashlynn Dunbar displays her sign with two young activists at a protest at the police department in Norman, Oklahoma, on June 2. (Photo courtesy of Ashlynn Dunbar)

That athletes exist for the sole purpose of fan entertainment is an idea steeped in racism — it's one often directed solely towards athletes of color. Take Ingraham, for example — the Fox News host who told James and Durant in 2018 to “keep the political commentary to yourself.” On June 4, after Drew Brees told Yahoo Finance that he disagreed with the peaceful protests by his fellow NFL players, Ingraham posited on her show, “He’s a person. He has some worth, I imagine. I mean, this is beyond football.”

The double standard isn’t lost on Dunbar. “What's the disconnect for you to think that Drew Brees has the right to have an opinion but LeBron and Kevin Durant don’t?” she says. “The really only difference that I'm seeing here is that Black male athletes can't have an opinion, but White male athletes can.”

“It's really easy to tell someone to be grateful when you haven’t experienced the history that they have.”

—Ashlynn Dunbar

Ingraham’s mentality is a microcosm of the thinking behind “stick to sports.” The crux of the message is rooted in the same ideologies that were used to maintain systems of slavery, segregation, and other forms of oppression: Be grateful.

Be grateful that you get paid or get a scholarship to play a sport.

Be grateful that we allow you to have your own water fountains and schools.

Be grateful that we provide food for you and your fellow slaves.

Be grateful.

“It's really easy to tell someone to be grateful when you haven’t experienced the history that they have — when you haven't been from the past that they have,” Dunbar says. “Whenever you have the ability to have this big platform and to make a difference and to change things that you want to see changed — because maybe you went through that when you were a kid and you don't want the same thing for the people coming up behind you — then we have every single right to feel like we want to continue and see change and make change.”

Making change has been Dunbar’s primary focus as of late. She’s been attending and speaking at protests, signing petitions and donating, posting on social media, and discussing social justice on podcasts. And she isn’t planning on stopping. “It's so important that when we get to return to our sports that this conversation does not die down,” she says. “This is still as relevant in the next few months as it is today, and it’s gonna continue to be relevant until there's change.”

Ashlynn Dunbar speaks to the crowd at a protest in front of Oklahoma University’s Evans Hall on June 6. (Photo courtesy of Ashlynn Dunbar)

Dunbar and many of her fellow Oklahoma athletes have been discussing how to maintain the momentum when their sports come back, and Dunbar has been involved in similar conversations with athletes from other universities as well. “As college athletes … we have so much power and such a powerful voice,” she says. “It's super encouraging because if anyone's gonna do it, it's gonna be my people — it's gonna be our generation.”

“If anyone's gonna do it, it's gonna be my people — it's gonna be our generation.”

—Ashlynn Dunbar

Dunbar’s generation is part of a growing movement of college athletes shedding the metaphorical muzzles and rising up against the narratives that have historically affected them the most. "Stick to sports" is dehumanizing to anyone, but college athletes — unpaid and unionless — have always had to bear the brunt of its perniciousness. "Some athletes … especially at the university level, feel intimidated and feel like they're unable to speak up without repercussions — without losing a scholarship, without not being able to play," Dunbar says. "That's just wrong … We can't be controlled."

As calls for social justice reform continue to sweep the nation, more and more college athletes are wielding their power for good. A group of University of Texas athletes released a statement on June 12 demanding several changes from the school to become more welcoming and inclusive — among them replacing statues, renaming buildings, and replacing the school song — and vowed to boycott recruiting and donor-related events until the changes are made. Oklahoma State football player Chuba Hubbard tweeted on June 15 that he “will not be doing anything with Oklahoma State until things CHANGE” after a photo surfaced of his head coach, Mike Gundy, wearing a shirt supporting OAN, a far-right news network known for promoting conspiracy theories and bashing the Black Lives Matter movement. The tweet elicited a public, albeit mechanically scripted, apology from Gundy. On June 26, a group of Kansas State athletes announced that they would not play until student Jaden McNeil, who posted a racist tweet making light of George Floyd the night before, receives “strong consequences.”

Fans, coaches, and athletic administrators probably won’t stop telling athletes in Dunbar’s generation to keep their political commentary out of sports any time soon. But to those who continue to cling to that tone-deaf mindset far past its expiration date, Dunbar has one response.

“Racism should not be political.”

Thanks for reading the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter. If you like our work, be sure to check out our stats site, our podcast, and our social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. You can also buy Her Hoop Stats gear, such as laptop stickers, mugs, and shirts!

Haven’t subscribed to the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter yet?