Thanks for reading the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter. If you like our work, be sure to check out our stats site, our podcast, and our social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. You can also buy Her Hoop Stats gear, such as laptop stickers, mugs, and shirts!

Haven’t subscribed to the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter yet?

When Hana Haden sat down at McAlister’s Deli to pitch one of her top recruits, she had no idea whether her presentation would work. Indya Green had “ghosted” her, as she now puts it, but the Moberly Area Community College head coach had tracked down Green’s father on Facebook to set up a meeting.

Green committed to Moberly, but Haden had to sell her on the idea of junior college to make that happen. Green’s biggest hesitation?

“I have great grades.”

“That's when I was explaining, like most of our players have great grades,” Haden says. “There's kind of that negative stereotype or misconception — they're like, ‘Oh, well, you know that it's like remedial classes.’ All of our classes are college-level classes; they're all transferable.”

It’s one of many common stigmas that JUCO carries. Bad grades, bad behavior, bad basketball … most JUCO players have heard it all. “I think they kind of have a little bit of a chip on their shoulder,” says Illinois State head coach Kristen Gillespie. “I think they try to disprove all those assumptions, whether it's academic or they got in trouble or they have baggage.”

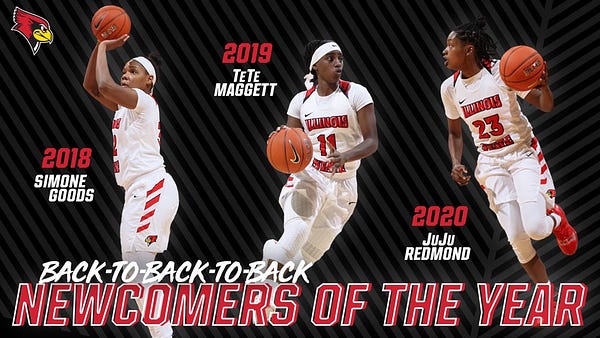

Gillespie has made a habit of bringing in JUCO talent during her Redbird tenure. In each of her first three seasons after arriving in 2017, the Missouri Valley Newcomer of the Year was one of her JUCO recruits.

“Our junior college kids have been some of the nicest kids, and you talk about unbelievable stories,” Gillespie says. “How do you not celebrate them; how do you not cheer for them?”

There are numerous reasons why players choose to start their college careers at a junior college, but lack of intelligence or character aren’t among them. In the case of FGCU guard TK Morehouse, she knew she could play Division I basketball, but not enough D-I coaches were willing to give the 5-foot-3 point guard a chance.

“When I was in high school, I wasn’t looking to go JUCO at all really,” she says. “As the years went on in high school and I wasn’t getting the [offers from] D-I colleges that I wanted, me and my AAU coach and my mom just sat down and discussed where I could elevate at. Western Nebraska [Community College] came out to be that school.”

Morehouse’s move paid dividends — she eventually got noticed by FGCU head coach Karl Smesko, and the rest is history. Last season she averaged 18 points per game for one of the best mid-major teams in the country.

“That’s what we tell kids: ‘Bet on yourself,’” says Haden, who can relate to being overlooked for her size. Before entering the coaching ranks, the 5-foot-4 point guard put together a playing career that included stops at three different schools from three different levels: D-II Missouri-St. Louis, Mineral Area Junior College, and D-I Western Carolina.

“Sometimes it makes people a little bit hesitant — the size,” Haden says. “I think junior college is a great opportunity to get on the floor and compete with and against other [future] Division I players to be able to prove yourself.”

Playing JUCO ball also provides a whole host of benefits for players beyond the opportunity to raise their stock. It offers a level of preparation that is often hard to come by at a four-year school. Many players have to wait their turn when they make the jump straight from high school to D-I — as freshmen they typically find themselves behind players three or even four years older than they are. That’s not the case at the JUCO level, where freshmen are frequently counted on immediately and sophomores are de facto seniors.

When JuJu Redmond joined Gillespie’s squad at Illinois State, she was entering a program that hadn’t been to a postseason tournament since 2013. But Redmond brought in more postseason experience than the rest of the roster combined. Her Tallahassee Community College team had won the NJCAA Division I national championship mere months prior.

Due to the setup of the tournament, it was Tallahassee’s fifth game in five days, a stretch most Division I teams never go through. “We didn’t think about being exhausted or tired,” Redmond says. “The championship game was just like, ‘We’re here and we shouldn’t let up and we gotta give it all we got.’”

For Morehouse, JUCO was a chance to expand her arsenal. “It was just a way to elevate my game and understand my style more,” she says. “When I came out of high school, I was just straight to the bucket; I didn't really think of pull-ups, midranges, and different aspects of the game.”

Playing heavy minutes on a JUCO power for two seasons is certainly a better opportunity for on-court preparation than sitting the bench on a D-I team, but JUCO players often enter D-I more prepared for the intangibles as well.

“When they get here, yes, they are kind of a newcomer so to speak, but they have already been equipped with tools to lead a team, so it's a little bit easier of a transition,” Gillespie says. “They're more comfortable finding their voice, where most freshmen are usually scared … they're more worried about what they have to do and where they need to go to say anything.”

Perhaps the most notable difference JUCO players have to acclimate to when they make the jump to D-I is the resources. Many D-I schools have several specialized staff members: video coordinators, strength and conditioning coaches, trainers, multiple full-time assistant coaches. That’s not the case at the JUCO level.

Haden has two full-time assistants, which she says is more than the majority of junior colleges have. But that’s the extent of the staff. “We’re still the three people for everything,” she says. “We monitor the academics, we're the ones holding the weekly meetings, we're the ones in the weight room, and we're the ones driving the bus.” Haden recalls her own JUCO coach washing the team’s jerseys.

“There’s nothing easy [at JUCO],” says Natasha Mack, who played two years at Angelina College before transferring to Oklahoma State and eventually getting drafted in the second round of the WNBA draft. “You don’t have the private planes, you have long bus rides to other colleges, you don’t have the strength and conditioning coaches. If you wanna go work out you will … [but] if you want to put in the extra work you have to do it on your own.”

Morehouse hasn’t taken anything for granted since she stepped onto FGCU’s campus. “I do feel spoiled coming to FGCU … We have shooting guns and stuff like that — things that I didn’t have in JUCO,” she says. “I really do appreciate all the things that come with playing D-I, but then I also can appreciate the humbleness that I got from playing in JUCO.”

It’s an appreciation that breeds a hard-working mentality unique to JUCO players. “We didn’t get a chance to moan and groan about not having stuff,” Redmond says. “If we got anything new, it was exciting, [because] we worked three times as hard to get it.”

That work ethic also stems from the short-lived nature of two-year schools. “At junior college, everybody’s hungry,” Haden says. “These players come here and there's a level of uncertainty on where they'll be [in two years], and they know it's really based on their performance.”

“I’ve seen some of the hardest working people at JUCO,” Mack added. “Your scholarships aren’t the same at JUCO as they are at D-I — some people just got half scholarships or no scholarships, so they really grind to try to get it.”

Then there’s the talent level, another facet of JUCO basketball that doesn’t get it’s due.

“The biggest adjustments were the really in-depth scouting reports and film breakdowns, and honestly the weight room,” Haden says of her transition as a player. “The basketball? That was probably the smallest adjustment.”

To understand the level of play on the JUCO court, one needs only to glance through the list of names that junior colleges have produced. Players like Danielle Adams and Shannon Bobbitt went on to win D-I national titles. Saudia Roundtree won multiple national player of the year awards for Georgia in 1996. Yolanda Griffith and Sheryl Swoopes were inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame. Each one took their game from a junior college all the way to the WNBA.

“People tend to overlook JUCO players,” Mack says. “There’s people in JUCO who definitely deserve to go D-I and get that opportunity.”

The world may not know it yet, but the players do. So as long as people keep sleeping on them, they’ll keep betting on themselves. And they’ll keep cashing out those bets.

Thanks for reading the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter. If you like our work, be sure to check out our stats site, our podcast, and our social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. You can also buy Her Hoop Stats gear, such as laptop stickers, mugs, and shirts!

Haven’t subscribed to the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter yet?