Fast, Competitive, and On the Rise: Inside the Women’s American Basketball Association

The semi-pro league aims to give more players a path to the WNBA or overseas

Thanks for reading the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter. If you like our work, be sure to check out our stats site, our podcast, and our social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. You can also buy Her Hoop Stats gear, such as laptop stickers, mugs, and shirts!

Haven’t subscribed to the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter yet?

In the 2019 WNBA Finals, Tianna Hawkins averaged 5.4 points and 2.6 rebounds per game to help the Washington Mystics win their first championship in franchise history. It was a monumental accomplishment for the DC native—yet, incredibly, Hawkins was not the only member of her family to help her hometown team to a championship last year. Just 16 days after Tianna and the Mystics triumphed in Game 5, her sister Tierra won a championship with the DC Cyclones of the semi-professional Women’s American Basketball Association (WABA).

The WABA, the sister league to the men’s American Basketball Association, was founded in 2017 to give women additional opportunities to play high-level basketball after college. “Everybody's not going to be able to play in the [WNBA],” said Faith Colter, the vice president of the WABA and a former player at Ithaca College. “The WNBA has [12] teams, [144 total] roster spots. So when you think of … the number of players coming out of college, that really doesn't afford a lot of opportunity.”

The WABA hopes to give players more exposure and game film that could convince overseas or WNBA scouts to sign them. Several WABA players have participated in WNBA training camps and/or are former WNBA draft picks, and WABA alumna Alisia Jenkins played in five WNBA games for three different teams in 2020.

The WABA season is relatively short, from August through October including the playoffs, and teams play about one game per week. As more teams are added, more games can be against regional opponents, which reduces the travel demands in a league that currently stretches from Massachusetts to Florida to Tijuana, Mexico. That is significant for the players because roughly 90% of them work other jobs, including as high school or college coaches, gym teachers, personal trainers, healthcare workers, and police officers.

The WABA has several rules that differ from the WNBA, most notably the “3D light.” The light is activated when a team forces a turnover before its opponent crosses half court. While it is on, the team that forced the turnover gets three points for a shot inside the arc and four points for a shot behind the arc.

“It brings a whole [new] level of excitement,” said William Flowers, the owner of the DC Cyclones. He recalled how, in the Cyclones’ first-ever game in 2017, they “were down something astronomical” but made a furious comeback on the strength of extra points from the 3D light. “It went from like 30 to 25, 25 to 20. And the fans were getting involved because everybody loves a good comeback,” Flowers said.

For the players, too, the 3D light raises the stakes of every possession. “If you're the recipient of the 3D light … all you hear [from the bench] is, ‘THREE!’” said Marsha Blount, the CEO of the WABA and a former Queens College player. “And if you are the team that didn't get that, you're yelling, ‘DEFENSE!’ because you don't want those extra points given. … So, if you're rewarded for playing defense, just imagine how much defense is played and how that increases the scoring.”

As a result of the 3D light and various other rules, many WABA teams press and trap, and games are often up-tempo and high-scoring. For example, the Atlanta Angels averaged 93.1 points per game in 2019 and scored over 130 points twice, and every WABA champion has scored more than 100 points in the final. Tabitha Richardson-Smith of the Jersey Expressions set the league’s individual single-game scoring record in September 2019, scoring 52 points on 24-of-36 shooting from the field. (In contrast, in the WNBA, the first 50-point performance didn’t come until its 17th season in 2013, only the 2010 Phoenix Mercury averaged more than the Angels’ 93.1 points per game, and no team has scored 130 points in a game.)

WABA rosters are a similar size to the WNBA—about a dozen players—but they are often filled through a combination of recruiting and open tryouts. Montgomery Lady Magic owner Adria Harris, who was previously the team’s head coach, recruited about half of her 2019 roster through connections she had from her time as an assistant coach at Alabama State. Most of her players were former Division I players, including Florida State alumna and 2018 WNBA draft pick Shakayla Thomas and former USC Upstate guard Kristen Dickerson.

Flowers tends to have more non-Division I players on his roster, which he believes reflects the talent at all levels of college basketball. His star player, Kyah Proctor, was the 2019 WABA MVP just over a year after graduating from Division II Bowie State, and Flowers is adamant that she is a WNBA-caliber player. “I'm doing the best I can to get her to play overseas because she deserves a shot,” he said. “… She's special. She just went to a smaller school.”

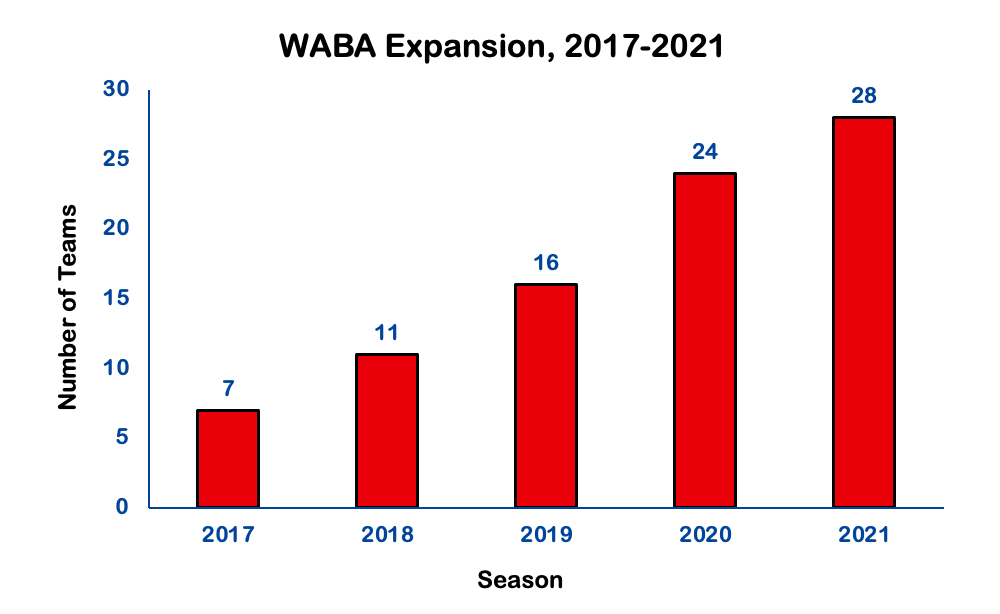

Driven by its mission to provide more opportunities for female players, the WABA has quadrupled in size over the past few years, from seven teams in its inaugural season in 2017 to 28 as of November 2020. (Expansion is still open for the 2021 season.) Yet there is still a waiting list of people who would like to own a WABA franchise, as Blount wants to ensure that all new teams have enough nearby opponents to build out a strong regional schedule.

One of the WABA’s newest teams is also its first international team, Las Dragonas de Tijuana in Tijuana, Mexico. The team’s owner, John Kidd, heard about the WABA’s expansion through his ownership of a men’s ABA team, Los Dragones, and reached out to Blount. For Blount, it was a good fit because Tijuana is just 20 miles south of San Diego—home to the WABA’s San Diego Sprint—and will help grow the league’s Far West region.

The emphasis on regional travel is part and parcel of a WABA business model that differs dramatically from the WNBA’s. “It’s affordable to own a team in the league,” Blount said, citing the WABA’s $12,000 salary cap, use of low-cost venues such as high school and college gyms, and lack of air travel until the championship game.

The business model is also grass-roots, as Blount and Colter generally focus on marketing and sponsorships at the league level while giving owners the freedom to build their teams as they see fit. “Marsha and her team … allow owners to really run their own organization,” Harris said. “… And I think when we bring all of our ideas and visions together and mesh, that's what makes it a great league.”

Many team owners, including Flowers and Harris, have used that freedom to develop their teams as community-based and family-oriented organizations. “This is a family environment. My family’s heavily involved in this. And so that's part of our culture,” Flowers said. He added that he has averaged about 70 fans by creating a game-day atmosphere that makes people say, “This is pretty cool. This is something to do with the family.” The energy of the players, the DJ providing additional entertainment, and the affordability of tickets ($5-$10) all factor into that calculation for fans.

Teams also leverage their local networks in their promotion efforts. Most players are either from the local area or played college basketball nearby, which aids in promotion and ticket sales, and they often raise awareness of the team and give back to the community through community service. Owners and coaches also reach out to area colleges to look for players and invite college teams to attend games. Harris advertises her team on local radio, television, and social media, and she even held a summer camp to expose the next generation of local girls to the WABA and inspire them to consider it in the future.

In 2019, former Armstrong State and current Atlanta Angels guard Deundria Clark became the league’s first brand ambassador and began to help promote and market the league in a more official capacity. “I just help the league grow, try to get new teams to join, as well as find … what's not working and what can make the league better,” Clark explained. “… This year coming up, 2021, we're gonna do a lot of different things.”

Unfortunately, those changes in 2021 will likely include new COVID-19 protocols. The WABA canceled its 2020 season due to the pandemic, and Blount and Colter watched how the WNBA and NBA adapted their models to inform the WABA’s thinking for 2021. Even if a vaccine becomes available early next year, Blount and Colter still expect that some precautions will be necessary, but the specifics will likely not come into focus until an owners’ meeting next May.

While necessary from a health and safety perspective, the stoppage in play has been difficult for everyone. Flowers said that the Cyclones had built up a buzz in the community over the years, culminating in their 2019 championship, but the lack of games in 2020 “put a halt to that rhythm.”

“We just have to, not necessarily start from scratch as far as putting butts in seats, but more so jumpstart the battery,” Flowers added. “… That part is the challenge.”

Some teams rode out 2020 by playing exhibition or charity games against local opponents outside the WABA. For example, the Montgomery Lady Magic recently played a home-and-home series with the Atlanta Legends, another semi-pro team, with one game doubling as a breast cancer charity event. Harris also hopes to schedule some guarantee games with colleges, which would give her team a financial boost and give both the Lady Magic and their opponents more playing opportunities during an uncertain time for all levels of sports.

The financial piece is particularly meaningful for a league as young as the WABA. Teams are not yet required to pay players, and those that do have various methods of allocating that money under the WABA’s salary cap. Atlanta Angels players have travel covered and are paid for winning Player of the Game or other incentives, while Harris, ahead of her first season as an owner, is still determining what will be possible for the Lady Magic. She explained, “Paying the players is important, but I think it's important to be in the position to be able to pay the players.”

As the league matures, one of Blount’s goals is to pay players more and eventually give them similar salaries domestically to what they might earn overseas. “So many [players] … are going overseas purely because of compensation,” Blount said. “And I think that we'll be able to play in the same ballpark and be able to provide those financial opportunities.”

The ultimate goal is that the WABA will one day be a developmental league, akin to the NBA’s G-League, that allows players to stay home while working toward a potential WNBA career. “I think that we're gonna be able to show that there's so much talent around the country that is not in [the] major league, if you will, because the WNBA is major-league,” Blount said. That may eventually involve capping the number of WABA teams, but at the moment, the WABA still sees room to grow.

One potential next step is more direct outreach to WNBA teams, particularly in cities that have teams in both leagues. “That's definitely a goal,” Clark said. “I feel like if we do reach out, they would be open to it.”

Some WABA and WNBA players have already connected during offseason workouts, especially in the Atlanta area. Many WNBA players live there in the offseason, and there are five WABA teams in the state of Georgia. The hope is that those interactions eventually lead to more conversations between WABA and WNBA coaches, scouts, and league executives.

“There is some knowledge of our game within the [WNBA],” Blount said. “I believe there have been teams that have had WABA executives at their games. We've had several WNBA legends at our championship games and actually help to present our Finals trophies.” In 2018, former New York Liberty great Teresa Weatherspoon did the honors, and her line of athletic clothing, Finisher, sponsored the WABA championship. But, Blount said, “we're still growing, not only our base but our exposure. And I think we have to … stay the course.”

In the meantime, the WNBA remains a strong influence on and a beacon of hope for the WABA. “A women's league in general is just an amazing thing to have, so we definitely look up to the WNBA,” Harris said. Blount added that, although the leagues’ business models are very different, the WABA tries to learn as much as it can from the WNBA. “We would love to be having [this] conversation 23 years later,” Blount said. “… They have the model, and it's been pretty successful.”

That model includes a groundbreaking collective bargaining agreement that the WNBA and its players association agreed to in January 2020. While the WABA is not at that point in its development yet, Blount appreciates the broader implications of that milestone for women’s sports. “We really do agree with what the WNBA players have been sharing about the fact that more income and more assets and more funding needs to be available for women's sports,” she said.

Seven months later, Blount and others in the WABA were particularly inspired by the WNBA players’ push for social justice during the 2020 season. Blount was “proud” to see the WNBA take a stand, while Harris said that empowering players to use their voice is “definitely something we have to do in the WABA.”

That may come as the WABA continues to gain exposure and momentum, but already, the mere existence of the league—not to mention its waitlist for team owners—speaks volumes about the potential for women’s sports in the United States. Like in the WNBA, Flowers said that getting fans to attend WABA games can be difficult, but once they do, most of them are amazed by all the league has to offer.

“I think the [WABA] shows that women's basketball is something to be reckoned with,” Flowers said. “… This league definitely shows the IQ, athleticism, talent—everything that you're looking for in basketball.”

Thanks for reading the Her Hoop Stats Newsletter. If you like our work, be sure to check out our stats site, our podcast, and our social media accounts on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.